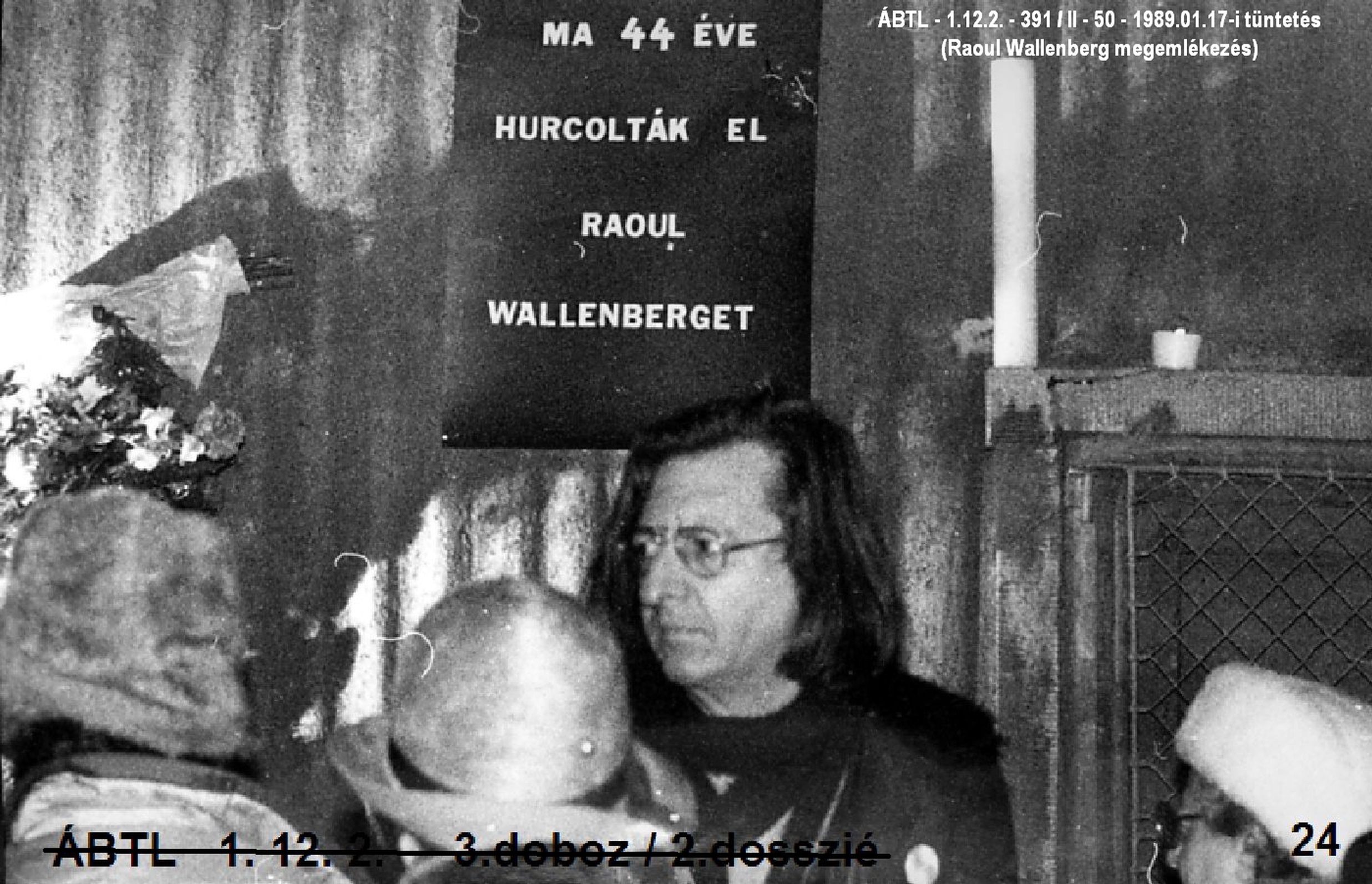

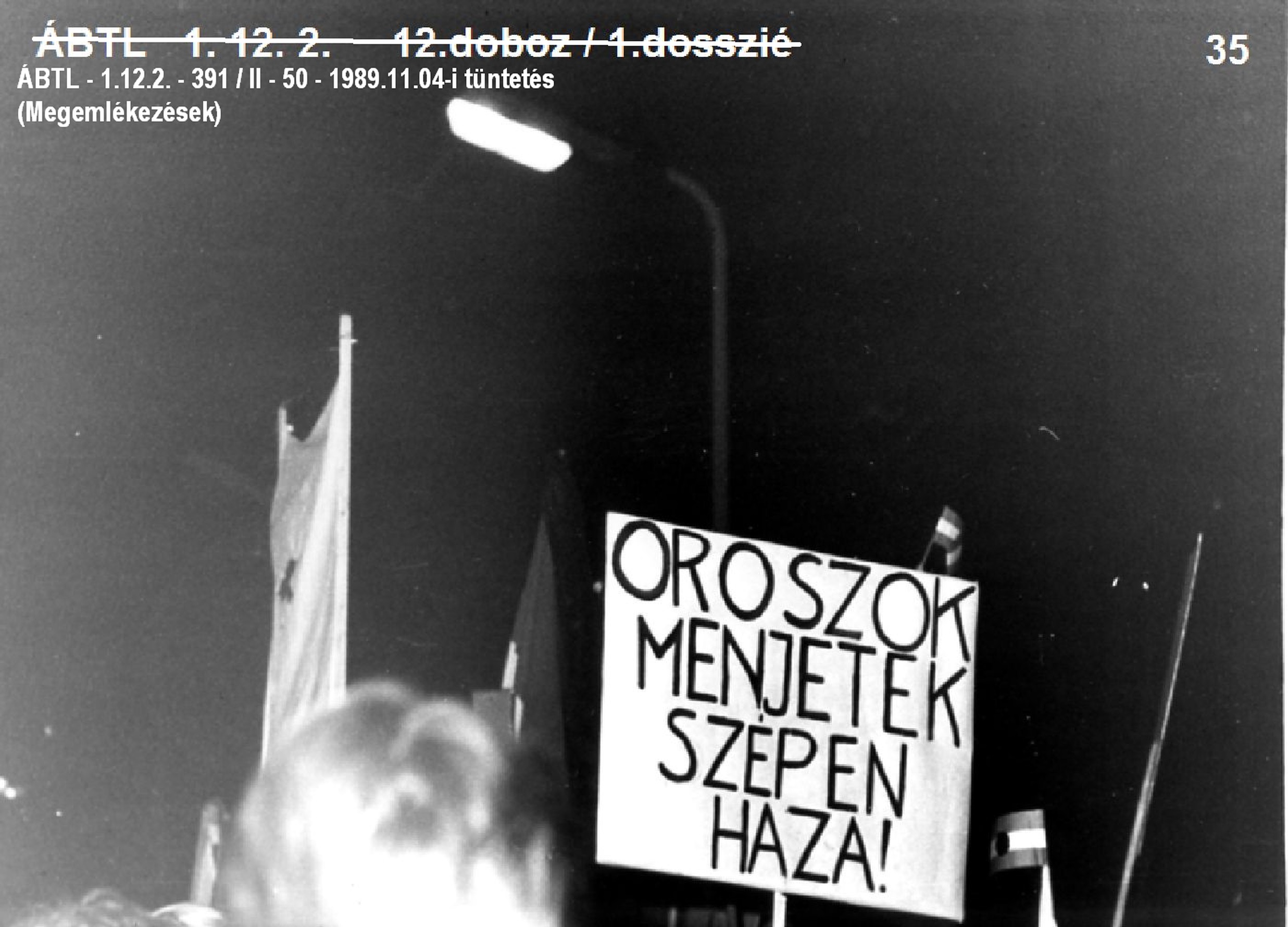

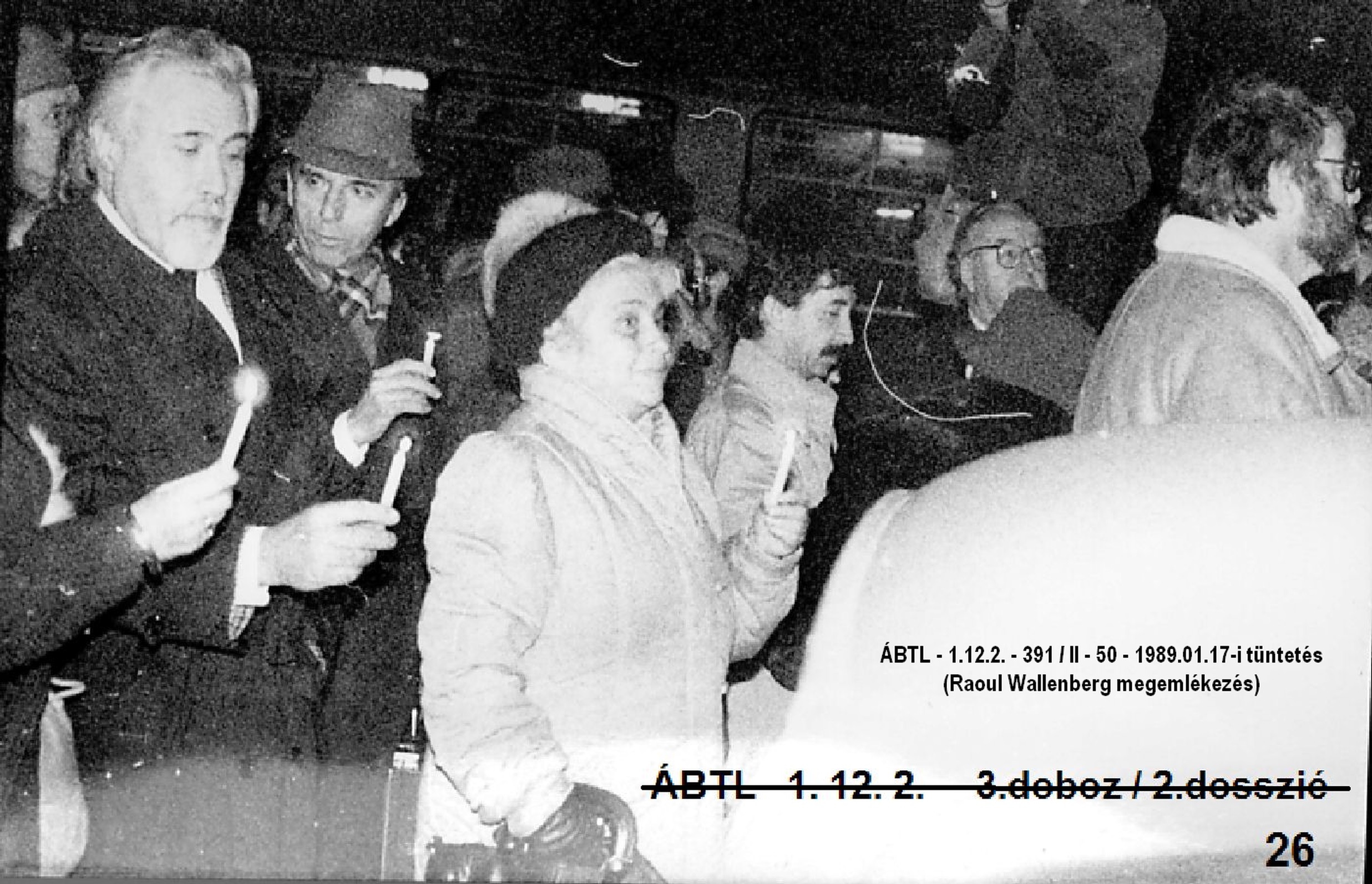

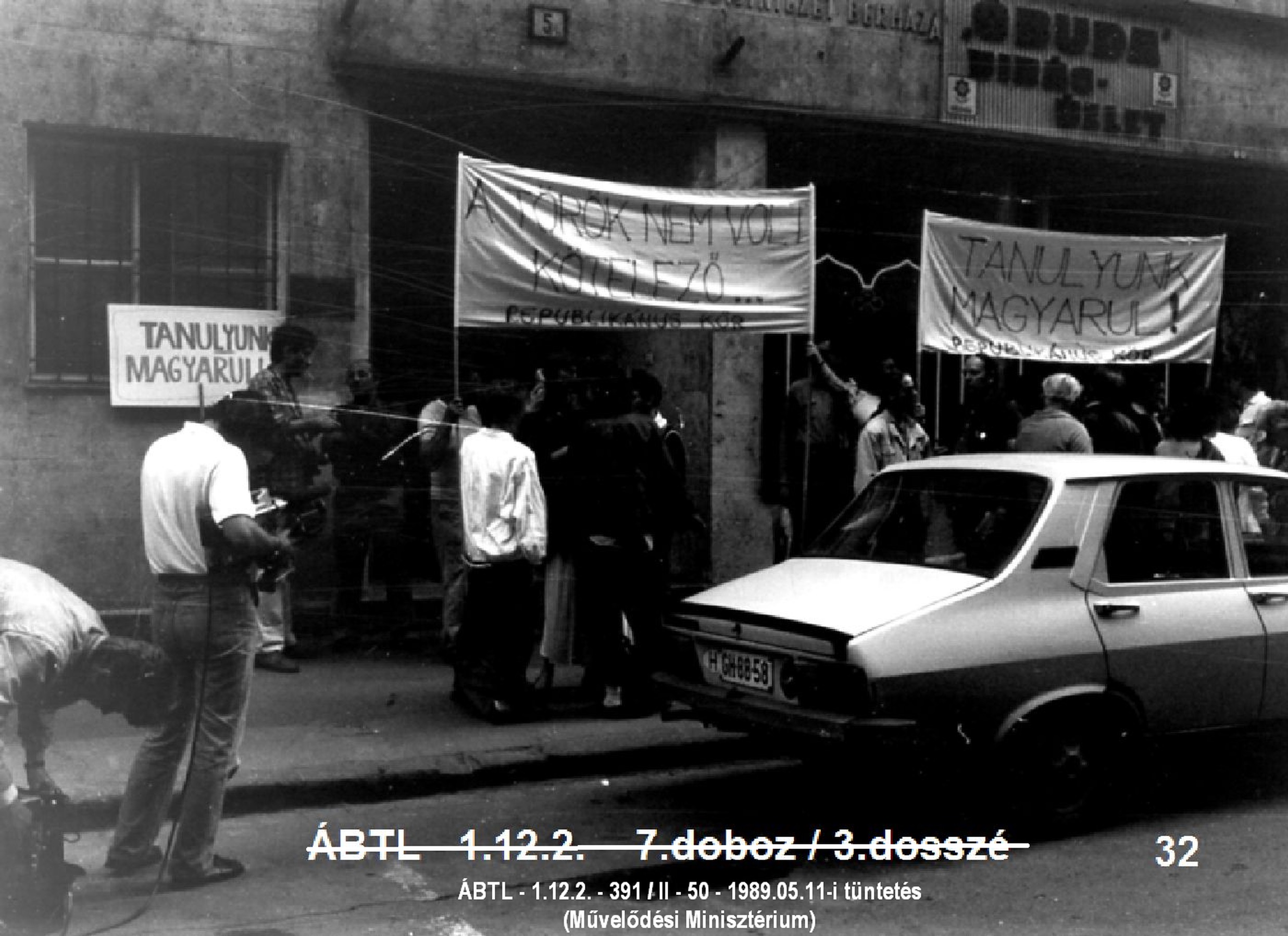

The boxes, entitled “Protests, demonstrations, actions,” are kept in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security (Állambiztonsági Szolgálatok Történeti Levéltára – ÁBTL). They include seven dossiers which contain photos and written documents. We can see photos of demonstrations which took place without exception in Budapest between January and November of 1989. Fortunately, we have some information concerning the creators of most of the photos. Thanks to Rolf Müller, a historian and state security photo-expert of ÁBTL, we can identify an agent with the cover name “Rolf Jenő” and a lieutenant, István Kurta. They took most of the photos of the different demonstrations.

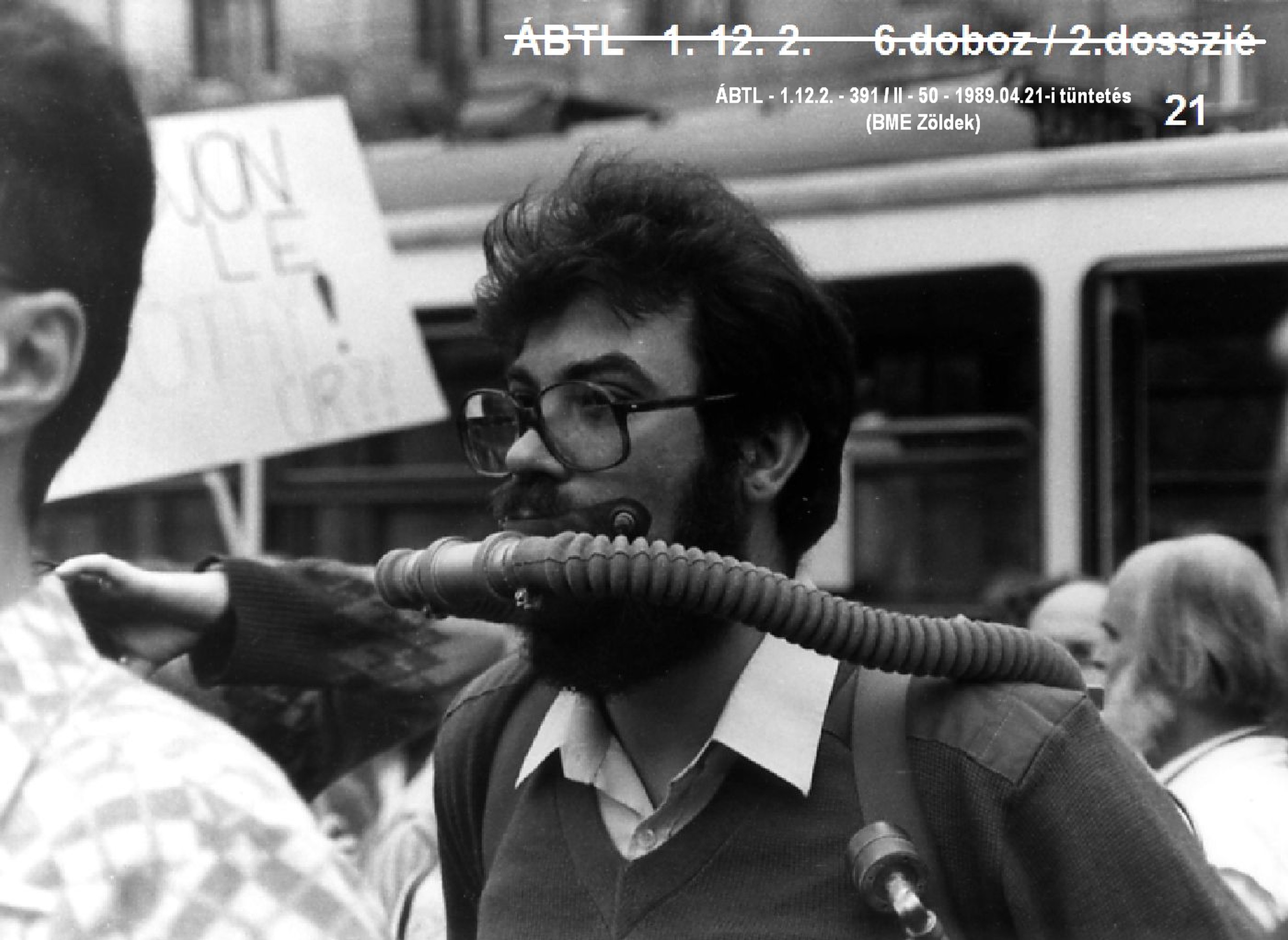

The communist political police constantly collected and created photos for evidentiary and prosecutorial processes, from the end World War II to the fall of the regime. An independent department dealt with visual documentation in the state security organization. How can ÁBTL photos help us reconstruct the cultural opposition within the framework of street actions? These records were not manipulated. They show what happened, because the photographers’ goal was to record individuals and banners so that they could be identified, so they sought to create as pictures that were as detailed and informative as possible. In some cases, leaflets and brochures were attached to the reports. It is possible that these materials would not otherwise have survived, so actually, the secret security people not only created sources (by writing reports and taking photos), but also discovered, collected, and preserved them. The written documents include reports, minutes, action plans, and summaries of methods and tools which shed light on the formalized regulations of the state security forces. The reports include data, events, texts of banners, descriptions of the behavior of participants and bystanders, and other events which attracted notice.

The Kádár-regime permitted organized public meetings only for official, politically supported goals in venues which had been checked and authorized. Anyone who broke these rules was seen as hostile by the police. The authorities tried to collect information about these plans and prevent the nonconformist actions. The experiences of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 were crucial for employers, police leaders, and the demonstrators.

In Hungary, the right of assembly was guaranteed by law beginning in January 1989. People were already free to go out and occupy public spaces, but during the turmoil, the agents of the secret police still observed the events by taking photos of the participants. A great number of photos are available to researchers in the Historical Archive. We do not know exactly why so many photographs were taken in secret. Rolf Müller contends that this reflects the endurance of earlier reflexess.

In 1988–89, at the dawn of the political transformation, dozens of demonstrations and protests were organized to promote different goals by civil, alternative groups, and activists. Political parties started to form. About 50 groups found street demonstrations an efficient way of representing their interest, goals, and protests to the public.

The purpose was to rouse society and demonstrate the power of these groups and to show the communist party that the demonstrators were able to act and express their opinion, and they could put pressure on the central political leadership. On the one hand, the actions marked historical anniversaries (the Revolutions of 1848 and 1956, the execution of former Prime Minister Imre Nagy, and so on). On the other, they were related to actual political, public issues and events.

Though these demonstrations enjoyed the support of many different organizations, there were still only between eight and ten of them. The groups fought for democratic rights and environmental protection, and they expressed their solidarity for the last people imprisoned by the agonizing dictatorships in Eastern Europe. Many of these events were located in the city center, especially on Vörösmarty Square. Eight demonstrations took place in the first half of 1989 and one in November.

The alternative artistic group Inconnu, the Jurta Theater, environmentalist clubs at universities, future political parties, and other smaller civil communities were among the organizers. The photo collections reveal that the issues stressed included solidarity with people who suffered illegal repression, people who had been arrested in other communist countries, and abuses of the rights of the Hungarian minority in Romania.