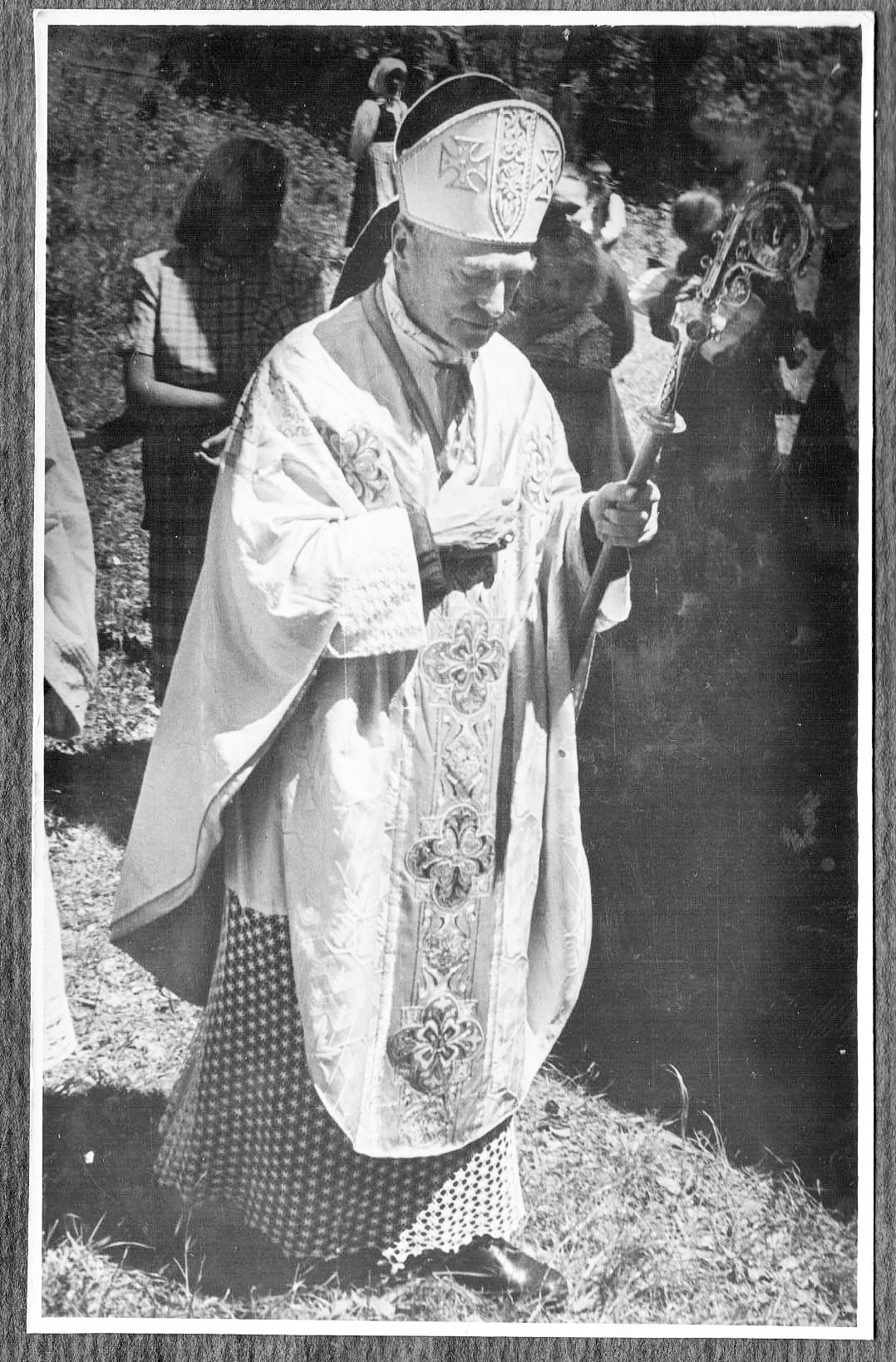

Áron Márton (b. 28 August 1896, Sândominic, Harghita county; d. 29 September 1980, Alba Iulia), bishop of Alba Iulia, the most influential Hungarian personality in twentieth-century Transylvania. He completed his secondary-school studies in Şumleu Ciucului, Miercurea-Ciuc and at the Károly G. Mailáth High School in Alba Iulia. In 1915 he was recruited for military service and he was discharged as a lieutenant. After the War he worked as an official in Brașov, and then from 1920 he was a seminary student in Alba Iulia. In 1924 he was ordained as a priest. He worked as a chaplain first in Ditrău, then from 1925 in Gheorgheni. From 1926 he taught religion at the public high school of Gheorgheni, and then from 1928 he served as a teacher of religion and assistant headteacher at the Catholic High School of Târgu Mureș. From 1929 he was a parish priest in Turnu Roșu and inspector of education at the Teréz Orphanage in Sibiu. After that he was a court chaplain in Alba Iulia for bishop Gusztáv Majláth. From 1930 he worked as an archivist, and from 1932 he held the position of episcopal secretary and he also worked as a university priest and homilist in Cluj. He was the organiser of extracurricular cultural education. Beginning with 1938 he was the parish priest of Saint Michael’s (Szent Mihály) church in Cluj. Pope Pius XI appointed him as bishop of Alba Iulia on December 24, 1938 and his consecration took place on February 12, 1939 (Domokos 1989; Virt 2002).

Following the Second Vienna Award the diocese was divided in two and Áron Márton remained in South Transylvania. The bishop was the only one during the Antonescu-government who dared to protest against the unequal treatment of Hungarians from Southern Transylvania. He was also the only person who presented the situation in an authentic manner to the Hungarian government. For three months, from November 1943 until January 1944 he visited the work camps set up near Făgăraș where some of the prisoners sent to jail without trial were specifically Germans and Hungarians. He officiated masses and helped those in need with pieces of clothing. On 18 May 1944, in his speech held in Saint Michael’s church in Cluj he protested against the deportation of Jews, and then a few days later on 22 May he sent a letter to the Hungarian authorities in which he asked them to prevent the deportation of Jews. After 23 August 1944 the bishop also visited the Hungarian intellectuals gathered as political prisoners in the work camps at Târgu-Jiu, Brad and other locations and on occasion he used his prestige to successfully intervene for people’s release. On 19 January 1945 he sent a letter to prime-minister Nicolae Rădescu in which he protested against the deportation of Germans (statement of József Marton; Marton 2014).

Even after the Second World War Áron Márton fought for the rights of the Hungarian minority, for freedom of religion and conscience. He tried to unite the leaders of the historical churches and in Cluj a memorandum was drawn up which proposed a more acceptable solution and asked that at least a part of the Transylvanian Hungarian population should be reattached to Hungary. The memorandum was signed only by Áron Márton. The content of the document which became one of the bishop’s main sins is known, as in the following month, on 8 January 1946 Áron Márton wrote an open letter of several pages to prime-minister Petru Groza. Giving an account of the impairments of rights (injuries), the situation, and state of mind of the Hungarian minority, he emphasised that he was not speaking on behalf of his community since he had no such delegacy. At the same time: “God created me a Hungarian and of course it hurts me to see the fate of my brothers and the evolution of their destiny cannot leave me indifferent. On the other hand, my priestly profession obliges me to weigh the issues also from the moral point of view. The situation of Hungarians living under Romanian supremacy does not comply with the great moral requirements laid down in the Statute of the United Nations as guiding principles of peaceful coexistence. And if we honestly want to promote peace between nations, I believe that we need to look for a way to see it unfold in this direction.” In 1946 the direct attacks began in the course of which Catholic priests were also persecuted and arrested. The bishop protested against this, too. On 18 March 1948, in the name of the Romanian Catholic episcopacy, along with his fellow bishops he turned to the minister of religious affairs in a letter, in which, due to the contradictions discovered in the Constitution, they argued in favour of freedom of conscience and religion as well as in favour of religious education and pastoral care. The new Constitution questioned the existence of religious denominations and Áron Márton realised that it was no longer possible to fight this alone so he joined the resistance movement organised around the nuncio Andrea Cassallo, who was later expelled. Áron Márton was asked to elaborate the Catholic Church’s statute, to be submitted to the state authorities. Out of the forty-six points of the draft, drawn up in a manner that was loyal to the Church, six were approved. In February 1949 the bishop reformulated the most important points but he did not receive an answer. As a reaction to the prohibition of the Romanian Greek Catholic church, Áron Márton called upon his priests in his circulars of 6 October and 20 October 1948 to offer the greatest possible support and help to their Greek Catholic brothers. At the time of Áron Márton’s death, Bishop Alexandru Todea thanked him in a separate entry in a memorial album for having assumed a role in the survival of the Greek Catholic church (statement of József Marton; Márton 2016).

On 21 June 1949 Áron Márton was arrested by the Securitate. At first he was kept in investigational detention, and then he was sentenced to life imprisonment by the military court in Bucharest on 13 July 1951. He served his sentence in the penitentiaries of Jilava, Aiud, Sighetu Marmației, and the Malmaison in Bucharest. After his sentence had been suspended by the Presidium of the Great National Assembly, he returned to Alba Iulia on 24 March 1955. As a result of the measures adopted by Áron Márton, who demanded discipline and work from his priests, the clerical peace movement collapsed. The bishop announced the great spiritual exercise, which had as its purpose to enable those who had fallen and succumbed during the “peace period” to settle their cases spiritually. The three-day spiritual exercise was followed by confession. The penitence was not in the form of prayers but consisted of money paid by those affected for the maintenance of the Faculty of Theology in Alba Iulia, which was in a very bad state. The situation was settled, and from then on, by virtue of an episcopal ordinance everybody had to accept the others. Áron Márton reorganised the Faculty of Theology, too. After his release, already in the autumn of that same year fifty theologians applied for posts, together with those who had earlier left the institution due to the collaboration of the Church leadership with the state authorities. Also at that time, Greek Catholic priests appeared, among them Lucian Mureșan, future archbishop and cardinal. Although the chorister school was established in 1953 in the so-called peace era, the bishop had planned its foundation already in 1948, so he approved and sanctioned the institution’s operating as a small seminary (statement of József Marton).

In the period between 1957 and 1967 Áron Márton was under house arrest and led the diocese from his episcopal residence. Among his responsibilities was the leading of the vacant dioceses of Satu Mare, Oradea, and Timisoara. Thanks to a short-term relaxation in the grip of the system his house arrest was eventually suspended. This was the time when he could undertake visits to Rome between 24 February and 6 March 1970, 6 and 26 October 1971, and 2 and 12 March 1974, on which occasions he had to settle certain matters. As a result of his visit in 1970, the possibility was created for at least four trainee priests or theology students per year to study in Rome. The most significant visit proved to be that of the year 1971, when Áron Márton took part in the episcopal synod and also held a speech. This is when he managed to obtain approval for the appointment of Antal Jakab as his suffragan. Jakab’s consecration as bishop took place in February 1972 in Saint Peter’s Cathedral, and received the approval of the Department of Religious Affairs as well. Succession represented the most delicate issue. Jakab was appointed with succession rights, cum iure successione, and was entitled to immediately follow Áron Márton in the position of bishop without the need for a new exchange of documents or further conciliation between the Romanian state and the Holy See. The visits to the Holy See meant a great experience and satisfaction to Áron Márton. He gave one to two-hour-long accounts of his journeys at the Theology Faculty in Alba Iulia so that he could spiritually strengthen his priests. It was important for theology students to maintain their optimism, knowing that they were taken into consideration in the better half of the world. Tragedy hit Áron Márton after his third visit to the Holy See, in May 1974. Following serious surgery he decided to adopt a more moderate work schedule and assigned part of his episcopal responsibilities to his suffragan (statement of József Marton; Márton 2015).

Áron Márton was also a man who embraced culture. It was no accident that as a young person he and the linguist Lajos György founded in September 1933 the pedagogical magazine entitled Erdélyi Iskola (Transylvanian school), which aimed at serving school education in the Hungarian language, the safeguarding of school and folk traditions and the utilisation of the more recent achievements in pedagogy. Last but not least they intended to help pedagogues in a period when teachers had no access to proper books as they lacked the necessary financial allowances. Although during his episcopacy the Church was confined within the walls of the church, to the vestry, Áron Márton strove to maintain contact with the personalities of culture and he welcomed the most outstanding Transylvanian writers, poets, and scholars – for example Andor Bajor, Sándor Fodor, Sándor Kányádi, and Samu Benkő – but also the more prominent experts in the field of science. As a consequence of the political changes they became questionable persons in the eyes of the party, but from Áron Márton they received much-needed support. The bishop maintained contact also with Hungarian poets and writers. He corresponded with János Pilinszky, and Gyula Illyés sent him his essay novel entitled Kháron ladikján (In Charon’s Boat) about growing old and dying, to which the bishop replied “You are not a faithless person, only a seeker.” The bishop gladly exchanged ideas with representatives of the opposition who would become black sheep in the 1980s. His guests were not only cultural personalities but also some persecuted persons who in case of need also benefitted from material support from the bishop. This is also a part of the cultural opposition. These people also represented human dignity in the face of the world. In 1971 – under the protective wing of the bishop – at the Theology Faculty of Alba Iulia a series of lectures was launched. Secular writers and poets came on Sundays to hold presentations beyond the regular curricular schedule. The initiative was banned already at the fourth presentation. Nevertheless, it was a great experience for the trainee priests to listen to Bajor, Fodor, Kányádi, or the traveller-writer Ödön Jakabos. The bishop was open toward everybody irrespective of confessional adherence. Áron Márton maintained contact also with persons of other nationalities and representatives of other confessions (Ozsvát 2003; statement of József Marton).

As of 1955, from his release from prison until his death in 1980, the bishop was under permanent monitoring and the Securitate tried to find out all of his initiatives and render all his anti-communist efforts impossible. His perseverance in resisting the interfering attempts of the state ensured the survival of the Church and of the Catholic faith and made him a moral example in the eyes of both his contemporaries and posterity. In the Archives of CNSAS (Romanian acronym for the National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives) there are four files relating to the person of Áron Márton, of which two are stored in the Penal Fonds, while other two are kept in the Informative Fonds. In the Penal Fonds the bishop’s name can be found on file no. P337 which consists of five volumes, comprising a total of 408 pages, and on file no. P254 consisting of twelve volumes numbering in total 4,544 pages. As far as the Informative Fonds is concerned, the following files can be found: file no. I261991 consisting of 174 volumes counting 54,.687 pages in total, and file no. I209511 made up of 62 volumes comprising a total of 22,393 pages. In this regard it must be mentioned that bishop Áron Márton has the largest amount of records of any individual in the Informative Fonds of CNSAS. As a comparison, the informative file of Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu who was the leader of the most significant anti-communist armed resistance group in all Romania comprises 119 volumes, while that of Ion Mihai Pacepa, the chief of the Directorate for Foreign Intelligence who fled the country in 1978, contains 120 volumes. According to Áron Márton’s observation files, the Securitate staff applied complex methods and means in order to collect information about the bishop between 1955 and 1980: they operated an intelligence network, monitored his activity with the help of technical means and the involvement of persons, controlled and censored his correspondence, made use of technical investigation instruments (Bodeanu 2014).

The communist authorities tried to prevent huge crowds from attending the funeral of Áron Márton in 1980. In his testament the bishop disposed that no funeral oration or special tribute speech in his honour should be given at his coffin. In his life he participated in all festivities, class-day ceremonies, and sport festivals. On the occasion of various commemorative events he received everyone including simple people and took photographs, and already during his life a certain Áron Márton cult was born which continued after the bishop’s death. The real driving force behind this was Lajos Bálint, who was elected suffragan bishop in 1981. In 1986 the first relief in memory of Áron Márton was unveiled at the Theology Faculty of Alba Iulia. The fiftieth anniversary of the bishop’s consecration was in December 1988 and the related ceremony should have been held in Cluj on 12 February 1989. However, this was prohibited by bishop Antal Jakab as he feared for his priests in Cluj. Eventually a night mass was officiated by the chaplain in Saint Michael’s church where it even pronouncing the name of Áron Márton was forbidden. However, two priests based in Cluj, Gábor Jakab and Lajos Szakács, in compliance with the agreement, received the intellectuals who used to hold lectures, i.e. Sándor Fodor, Sándor Kányádi, and György Beke. Later on both priests were denied their state allowances. Immediately after the fiftieth anniversary of the bishop’s consecration, suffragan Bálint wrote in January 1989 a circular in which, hiding behind quotations from Áron Márton, he alluded to the dilemma of exodus vs. remaining at home, which the Hungarians of Transylvania faced in the late 1980s, but this could not be published either. The future archbishop eventually transcribed these into sermons and published them only later in the Áron Márton Memorial Book of 1996. After the collapse of communism, the already-existing strong esteem for Áron Márton intensified. Following the change of regime, squares, streets, and schools were named after Áron Márton as a sign of public respect. The first studio documentary about the bishop’s life was made by Gábor Jakab and Gábor Xantus in 1993–1994 and carried the title: With his Head Held High: A Documentary about the Life and Career of Bishop Áron Márton. In 2003, on the occasion of the temporary exhibition of the House of Terror in Budapest entitled Áron Márton (1896–1980), a twenty-five-minute film was made on the life and activity of the bishop. On 16 October 2010, the Áron Márton Association of Sândominic, the Sândominic local government and the Roman Catholic Parish House of Sândominic inaugurated the Áron Márton Museum under the leadership of archbishop György Jakubinyi and coadjutor József Tamás. Today this is the most comprehensive museum collection about Áron Márton, also including audio guides. In March–April 2012, director Cristian Amza made a movie entitled Marton Aron, un episcop pe drumul crucii (Aron Marton, a bishop on the way of the Cross). In 2013, on the seventy-fifth anniversary of Áron Márton’s consecration as bishop, by courtesy of the Gábor Bethlen Fund, the ground-floor room in the truncated tower of Alba Iulia Cathedral which had already been furbished earlier as an Áron Márton memorial room, was complemented with two touchscreen info-terminals: one is placed in the exhibition hall, while the other is located in the cathedral (statement of József Marton).

Although the priests ordained by Bishop Áron Márton have by now mostly retired or died, their teachings have been adopted by the younger generation and the respect for Áron Márton continues unbroken. Religion teachers organise Áron Márton contests and the life of the bishop is known to everybody in the Transylvanian Roman Catholic diocese. The purpose is to promote a proper esteem, not by exaggerating but by remembering the real qualities of the man and of the bishop: the sincere, straightforward, helpful bishop living for others. In 1991 his beatification trial began. Today he is designated the Servant of God, which is the name of a candidate for beatification, and the first step in becoming a saint (statement of József Marton).