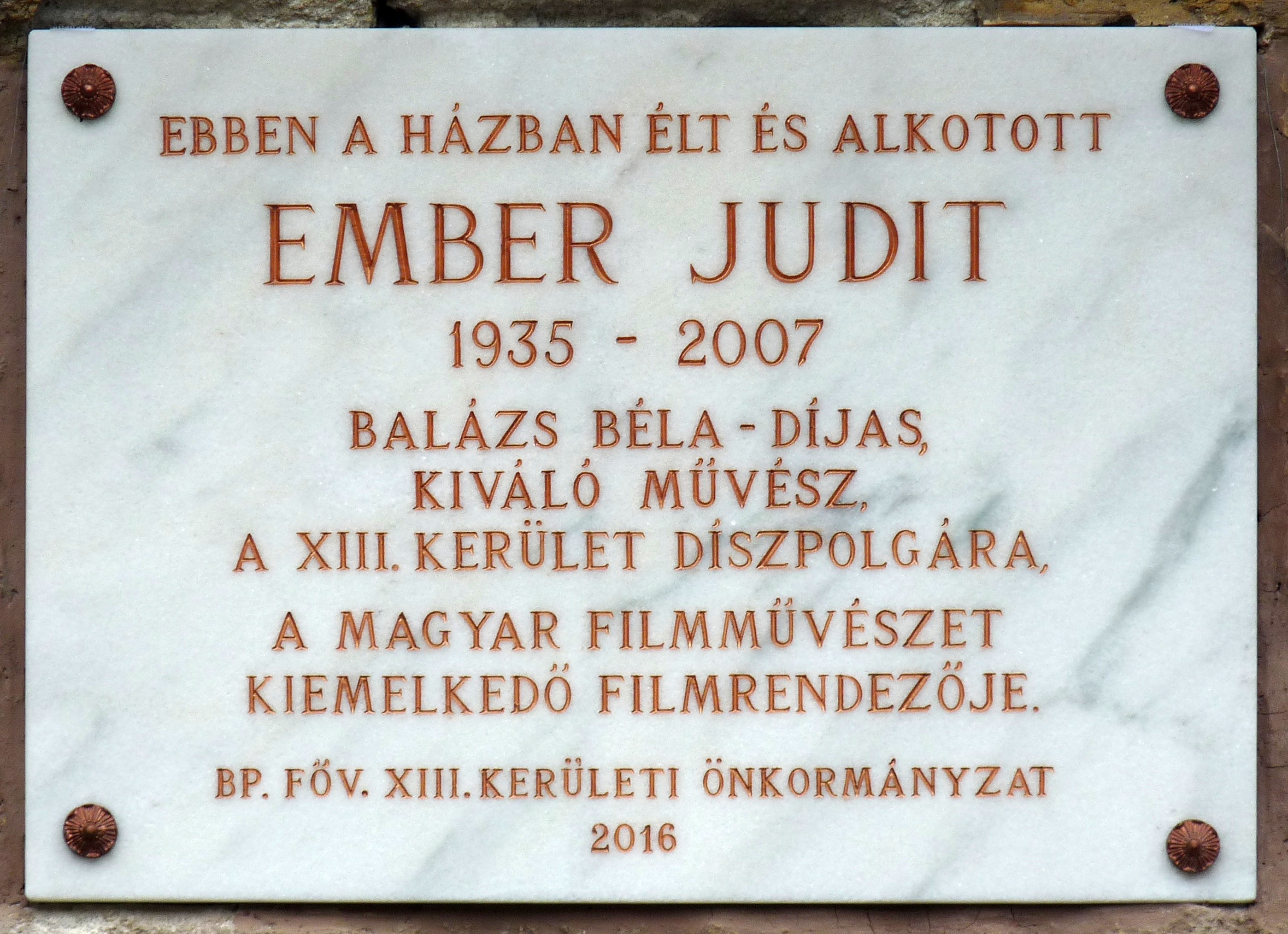

Judit Ember (1935–2007) was an independent film director, founding staff member of Black Box video periodical, and director of many taboo-breaking and banned documentary films during communist rule in Hungary

She was born in the village of Abádszalók and brought up in an assimilated Hungarian Jewish family. Her father was a lawyer, who was killed in Auschwitz. The rest of the family managed to survive the Holocaust and avoided being deported to the extermination camp through a fortuitous chance.

She studied Hungarian language and literature and history at Loránd Eötvös University, Budapest, then continued her studies at the College of Theater and Film Arts, where in 1968 she received a film director degree. She started her professional career at the Popular, Scientific, and Educational Film Studio, MAFILM, then from the 1970s she worked for Hungarian Television and the Béla Balázs Studio (BBS). As a filmmaker, she belonged to the trend of “situative documentarism,” a new genre that some young and talented artists cultivated at BBS, the essence of which was to explore or reconstruct a real-life situation by exploring the historical and sociological roots of the course of events.

Ember, with her mind and attitude, was a real independent filmmaker right from her earliest works. She preferred to choose topics that the official media neglected or misrepresented, or did not even dare to touch. As she said: “What is at stake here are the traumatic experiences of a whole society, which accumulated, stockpiled, and were never discussed publicly. It is a society which contains not a single group or layer that did not suffer from injustice and prejudice in the 20th century, nor from being hit, humiliated, persecuted, expulsed, or even killed.”

In Hungarian film history she remains the director with the record number of banned movies, such masterly works as “Stage” (1968), The Resolution (1972), “Case Study” (1976), Pócspetri (1982), and “Let Kutrucz Talk” (1985). Critics consider most of her films to be both artistic and social scientific case studies. Her special style, original method in dramaturgy, and exciting inquiries are the main characteristics of her works, together with much empathy and a genuine talent in bringing out the feelings and thoughts of her everyday characters. It is a small wonder that she became one of the founding members of Black Box.

She felt it her moral duty to give voice those who were never asked to speak or did not have a chance to express their views. She had a special talent in bringing out difficult testimonies of her amateur characters, with a sensitive reception towards their experiences and autobiographical stories. With her empathy and psychological knowledge, she perfectly knew that without letting the patient talk there is no recovery. However, apart from empathy, something else was also needed for Ember to give voice to her characters, those peasants deprived of their small lands, and who were then frozen in fear and shame for the rest of their life, or the intellectuals who spent years in prison and were well aware of the risk of speaking publicly about the regime’s crimes. This extra factor was simply Ember’s human quality, her confidence, tactful and patient presence, expressing silently that she trusts in the speaker’s rightful cause, and thus managed to persuade everybody that it was well worth it to talk freely about those painful events after thirty years’ silence.

Éva Vass, a film preservationist at the Hungarian Film Archives, remembers Judit Ember as someone who did not seek the absolute truth, but rather preferred to reconstruct events from the viewpoints of everyday people. “Her method always follows the uncertain trail of the exploration of reality, as she drags her spectators into the story, and after a while they feel as if they were also being questioned, becoming participants of those real-life events too. And what is most fascinating in her films is the depth of this presentation.”

Judit Ember received the Béla Balázs Prize in 1989 and earned a number of foreign recognitions for her works. Her documentary film

The Resolution was called by the American Film Academy in Los Angeles one of the “Hundred Best Documentary Films Ever Made.” The Hungarian filmmakers’ society also paid tribute to her memory in recognition of her work. A monograph was published about her oeuvre entitled

Ember-Lépték (“Human Scale”). Since 2008 the main prize of the Documentary Category given yearly at the Hungarian Film Festival is named after her as the Judit Ember Prize.