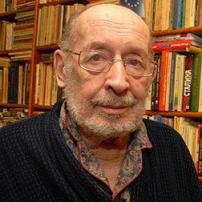

Mihajlov, Mihajlo

Mihajlo Mihajlov was born in Pančevo on 26 September 1934 to a family of Russian émigrés, Nikolai and Vera (née Danilov), who settled in this small town near Belgrade in the decade after the October Revolution. His father, despite being a member of the Russian Tsarist emigration, participated in the Partisan movement under the leadership of the Tito’s communists, so that the path to the newly formed communist elite was wide open to the young Mihajlov. He graduated from the real gymnasium for boys in Sarajevo in 1953. After that, he attended the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade, where he studied world literature and English for five semesters (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 1).

After a short interruption of his studies, he worked as a journalist for the Sarajevo newspaper Oslobodjenje for a time. He continued his studies in Zagreb in 1957 at the Department of Comparative Literature. In 1959, he successfully graduated from the Faculty of the Humanities in Zagreb. He then worked as a translator and writer in Zagreb at the beginning of the 1960s. In 1960, he received a scholarship from the Croatian Cultural and Research Council for Postgraduate Studies at the Slavic Institute of the Faculty of Humanities in Zagreb under the mentorship of Prof. Aleksandar Flaker with a thesis on “Russian Prose in the Period of Disintegration of Russian Realism.” From January to March 1963, he was employed as the honorary director of the Grič Gornji Grad National University in Zagreb. In 1962, he was earned his doctorate under Prof. Flaker with a dissertation on "Causes of Motivations in the Treatment of Figures in the Works of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky" (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 1).

He spent the period from 1963 to 1966 in Zadar as an assistant lecturer on Russian modern literature, where he confronted with the regime and its ideology. In 1964, he went on a study leave in the Soviet Union, after which he published two essays under the headline “Moscow Summer” in the Belgrade magazine Delo in January and February 1965. These texts were soon criticized by President Tito himself, due to the literary description of the contemporary circumstances in the Soviet Union. Namely, the fall of Nikita Khrushchev occurred just before the publication of these controversial essays, which made Mihajlov's “Moscow Summer” politically sensitive to the Yugoslav authorities, which at the time were investing intensive efforts to stabilize relations with the Soviets (Mihajlov Mihajlov Papers, box 1).

Mihajlov was incarcerated a second time as a result of his initiative in December 1965 together with a group of Zadar intellectuals to establish the first publication outside of Party control called Slobodni glas (Free Voice), which would advocate for the democratization of the socialist regime and the introduction of intellectual and political pluralism in Yugoslavia. Mihajlov advocated for multiparty democracy based on the Western model, because he had concluded that every single-party system, even as liberal as the “Yugoslav example,” was ultimately a “sub-type of Stalinism.” Mihajlov repeatedly demanded that “socialist democracy” in Yugoslavia be abolished and replaced by "democratic socialism" that would allow the political organization of other parties and the limited development of private property. In terms of political pluralism, he emphasized that only "sick societies" had political emigration, while “healthy societies” have their own political opposition (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 1).

He opposed the revolutionary transformation of society, so he therefore proposed a gradual evolutionary process to change Yugoslav socialism. Religion, above all Orthodox Christianity, was on his mind in particular, so he thought that the teaching of Christ and Paul opposed Tolstoy's pacifism, for unlike them he did not inspire him to fight against the evil, as Mihajlov characterized his own struggle against the totalitarian regime in Yugoslavia. Based on this, Mihajlov approached the idea of Christian Socialism, clearly opposing the atheistic socialism that prevailed in the countries under the dictatorship of communists throughout Eastern Europe. That was why he believed that a fundamental critique of this type of socialism had to begin with criticism of atheism (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3).

The culmination of the efforts of Mihajlov’s Zadar group was the Declaration of the Steering Committee of the Socialist and Democratic Free Voice in August 1966. Mihajlov was first attacked by the Belgrade daily Politika, which labelled him a “religious fanatic,” “a Djilas adherent” (Đilasovac) and a Western agent after he was arrested and the establishment of his magazine was barred. In the trial in Belgrade in 1967, he was accused of calling into question the one-party system, advocating democratic socialism, establishing a Christian socialist party and trying to initiate a free non-party publication.

His initiatives were indicted as “enemy propaganda,” for which the Belgrade court sentenced him to four and a half years in prison. Later, it was reduced to three and a half years on April 19, 1967. In Mihajlov’s case, the abuse of the psychiatric profession was also involved, so that the verdict included this allegation: “the psychopathic personality was insufficiently prepared for social adaptation.” His defence attorneys at the trial, Ivo Glowatzky and Veljko Kovačević, were from Zagreb and Belgrade (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3).

He was in prison from November 15, 1966 to March 4, 1970, naturally losing a professorship at the Faculty in Zadar. Immediately after leaving prison on May 14, 1970, he applied for a passport which was subsequently rejected by the authorities. On May 7, 1971, the authorities in Novi Sad officially refused his application for a passport, which he appealed on May 12, 1971 before the Provincial Secretariat for Internal Affairs in Novi Sad. In that period, he lived in Belgrade and wrote for the Western press, whence he received financial support (Mihajlov Mihajlov Papers, box 3).

After leaving prison, he continued his own interrupted research work for his doctoral dissertation on Dostoyevsky. Due to the regime’s repression against Croatia after 1971, Mihajlov decided to pursue his doctoral work in the somewhat “more liberal” Slovenia at the University of Ljubljana under the mentorship of Dušan Pirjevac Ahac. Since the authorities prohibited him from writing publicly for four years, Mihajlov was later sentenced to 30 days in prison in 1972 because he had published the article “The Artist as the Enemy” in The New York Times (February 1, 1971) and two letters to the Herald Tribune (October 1970 and February 1971) (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3).

Mihajlov discussed Marx's idea of alienation with Djilas in the article “Djilas versus Marx. A Theory of Alienation” in 1972 (Djilas and Marx, Theory of Alienation), Survey 18 No. 2 (1972): 1-13. In it, Mihajlov noted that despite the fact that Djilas distanced himself from official Marxism he remained an heir of Marxist thought when he said freedom is the consequence of historical development, not its precondition and cause. Therefore, in Mihajlov’s letter from the summer of 1973, he criticized Djilas' critique of Christianity and his lack of understanding of the relationship between religion and atheism in the future epoch (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3).

Such a view of Djilas rested on the fact that Mihajlov was not at all a Marxist thinker, but rather a Christian-inspired modern intellectual who, under neoclassical socialism and democracy, sought inspiration in the Christian philosophy of the world. Seeing himself as belonging to the Russian people and culture, in 1974 he debated the famous Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn about his Letter to the Soviet Leaders. Solzhenitsyn reasoned that the Russian alternative was not to accept the Western European model of democracy, which diverged from to Mihajlov’s view, who said it had Christian origins. On the contrary, Solzhenitsyn believed that it would result in anarchism and materialism, which were foreign to Russian traditions. In this regard, Mihajlov was very critical of Solzhenitsyn's concept of the “altruistic authoritarianism” that would be established after the fall of the Soviet communist dictatorship (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3). In these discussions, Serbian political émigrés saw Solzhenitsyn and Mihajlov as two opposing representatives of anti-communism, with the former believing that communism could only be overthrown by national revival, while the former advocated for a process of internal democratization and liberalization of communism, seeing the menace of nationalism in a national revival (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 30).

Regarding internal Yugoslav circumstances, while in exile Mihajlov later advocated for the unconditional preservation of the integrity of the Yugoslav state, thinking that Yugoslavia as a country was a favourable solution, primarily to the Serb and Croat national question, but also to its democratization and the introduction of political and economic freedoms. In the 1970s, Mihajlov predicted that far-reaching changes in Yugoslavia would come only after Tito's death, when the inevitable de-Titoization had to proceed, as in the Soviet Union after Stalin's death. Mihajlov realized that the support of Western democracies for Tito's dictatorship, which was still associated with the positive connotations of Yugoslav “liberalization” in the 1960s, would be an obstacle to such processes. By contrast, in the period after 1972 and the quashing of Croatian and Serbian “liberals,” this support became a negative feature that prevented necessary changes to the Yugoslav system. It is noteworthy that his thought on this was influenced by the main representatives of the Russian inter-war emigration, such as Nikolai Berdyaev, while he was inspired by Djilas’ model in the Yugoslavian context (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3).

Between his releasing from prison in 1970 and his departure into exile in 1978, Mihajlov clearly pointed out in correspondence with Djilas that he had no political ambitions, but rather solely fought for the freedom of thought and expression in the intellectual and cultural spheres of life: “I have no ambition toward any kind of participation in power in the territory of Yugoslavia, although I have, of course, some demands for freedom to act in the intellectual, ideological and religious spheres” (Letter from Mihajlov to Djilas, July 1973, Novi Sad, Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, Box 3).

He published his second work, “Russian Theme,” in 1968, two years before leaving prison in 1970. After settling down in Novi Sad, he contributed to the Western and Russian émigré press (Seedtime and Russian Thought). In October 1974 he was arrested again and sentenced to seven years in prison. Mihajlov observed his trial from prison, which was an evident violation of the legal standards of civilized countries. Numerous human rights groups from the West appealed to President Tito to grant him amnesty. He spent three years and two months in the prison in Srijemska Mitrovica, from which he released on November 25, 1977, along with 218 other political prisoners. This was the result of pressure from the international public and the human rights movement, as the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe was being held in Belgrade at the time.

After leaving for the USA in 1978, where his mother and sister were already residing, he received the annual award of the International Human Rights League in that same year. He lectured on Russian philosophy and literature at several Western colleges until 1985. He also lectured at many universities in North America, Europe and Asia, speaking about his dissident experience and similar issues from the field of Russian cultural history at Columbia, Berkeley, Cornell, McGill and the London School of Economics. In 1981 he was a visiting professor at Yale University as an expert on Russian literature and philosophy, and he taught at the University of Virginia in the academic year 1982-1983. He was also a visiting professor at Ohio University in 1983-1984, then at Siegen University in 1984, and finally at the Glasgow School of Science in 1985. He wrote for the New York Times, New Review of Books, New Leader, Reader's Digest, and other Western journals and reviews (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 9).

During the 1980s, he played an extraordinary role in strengthening the dissident movement in Yugoslavia when, together with Milovan Djilas and Franjo Tudjman in 1980, he founded the Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (CADDY) under the patronage of the Democratic International in New York. As a founder of the bi-monthly CADDY bulletin, which was edited in English until 1992, he continually testified to the status of dissidents, political prisoners and human rights in Yugoslavia. Apart from the Yugoslav scene, Mihajlov also participated on Russian émigré and dissident scene, publishing essays and papers in the Russian émigré press and communicating with Soviet dissidents. In all of these public appearances, he expressed his Christian and social democratic worldviews. While the Soviet Union considered restoring Solzhenitsyn’s citizenship in 1988, in the same year Mihajlov was deprived of citizenship by the Republican Secretariat for Internal Affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was accused of disseminating enemy propaganda against Yugoslavia in the West (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 3). Only two years later, the Yugoslav government restored his citizenship just before the democratic elections in Serbia in 1990.

After his university career, he worked as a commentator and analyst on intellectual and ideological issues for Radio Free Europe from 1985 to 1994. In the following year and until the end of the 1990s, he lectured in a program on the transition of former communist regimes to democracy at the Elliot School, Georgetown University. He was a sharp critic of Serbia's role in the bloody break-up of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Mihajlov hoped for the survival of the Yugoslav state and opposed separatism in the Yugoslav republics. In that sense, he condemned his colleagues, former Belgrade dissidents who supported Milošević's “anti-bureaucratic revolution” and his efforts to resolve the Yugoslav crisis by force. He lived in exile for a rather long period, until the fall of reformed communist regime of Slobodan Milošević in October 2001, when he finally returned to the then Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During the Milošević era, he supported the Serbian opposition and the founders of the Democratic Party (Zoran Djindjic, Vojislav Koštunica, Kosta Čavoški, Slobodan Inić, Borislav Pekić, Miodrag Perišić) during his very short visit to Yugoslavia in October and November 1990 (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 8). After the fall of Milošević’s regime in October 2000, he permanently returned to Belgrade, where he was actively engaged in public life until his death. He died in Belgrade on March 7, 2010 at the age of 76.

Asukoht

-

Belgrade, Serbia

Näita asukohta

Sünnikoht

- Pancevo, Serbia

Sünnikuupäev

- 1934

Surmakuupäev

- 2010

Lehekülje autorid

- Kljaić, Stipe