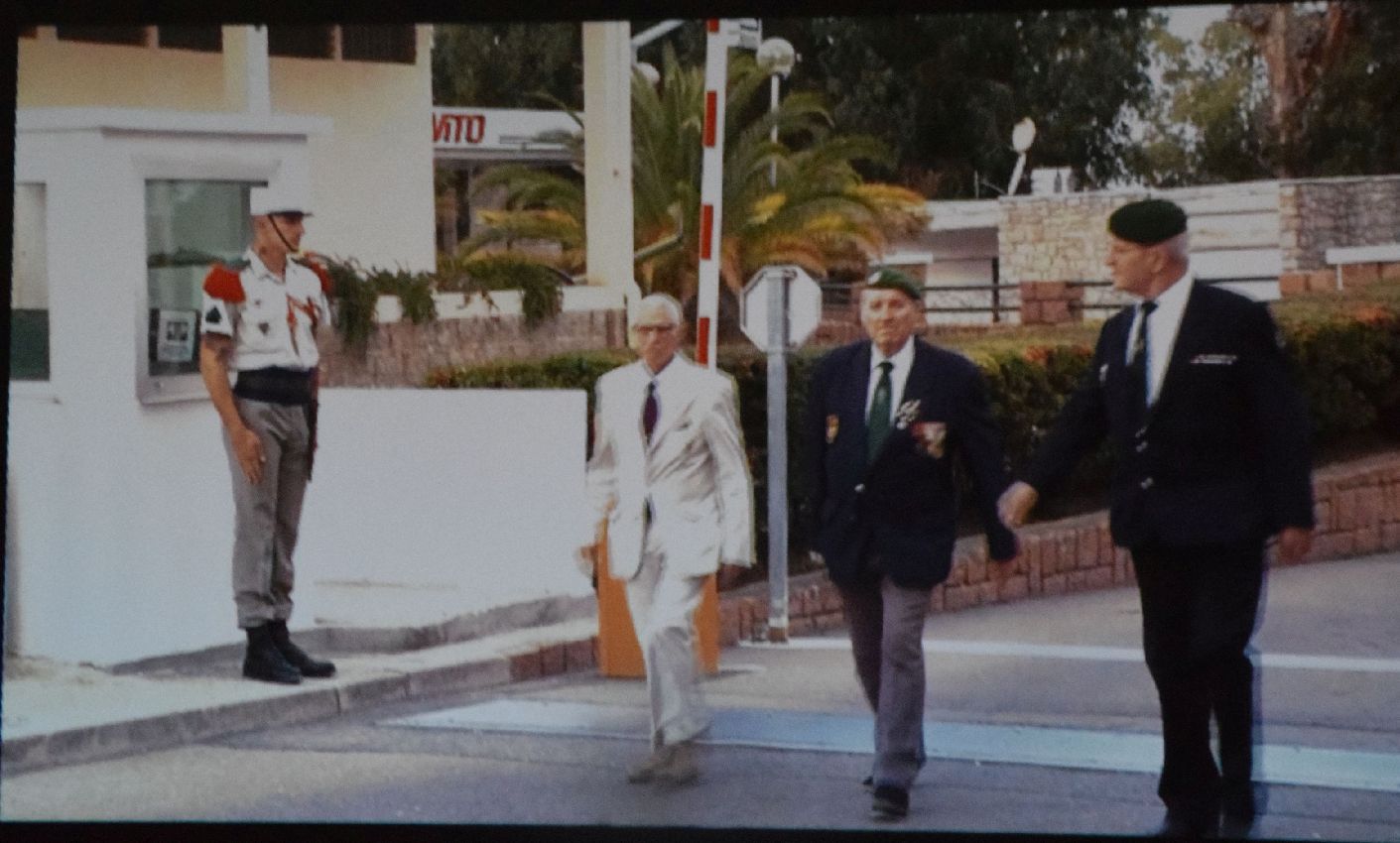

The five years of research in both Hungary and France between 2011 to 2016 uncovered substantive sources about those Hungarian refugees who as minors fled to the West in 1956 and a few years later joined the Foreign Legion. Of the estimated 500 who enlisted in the French colonial corps following 1956 Hungarian revolution, the historian and documentary filmmaker Béla Nóvé managed to identify more than the half of them: altogether 269 volunteers with names and personal data. (The complete headcount of Hungarian legionnaires in the period is estimated at 3,000.) In addition to a great number of secret counter-intelligence documents—agent and police reports, archive letters and photographs, minutes of interrogations—he extended his research to the Legion’s Central Archives in Aubagne, where no Hungarian scholar had been received before. Moreover, in the summer of 2011, Béla Nóvé was lucky to find a circle of Hungarian veterans in Provence, with whom he compiled oral histories and completed a documentary film and book, both with the same title, Patria nostra. They had all fled as minors in late 1956 and served 15 to 30 years in the Legion. Today they are part of a veterans’ community of around 25 members in Provence and some 70 throughout France.

The sources all suggest that, apart from their common early experiences, each legionnaire had a very different career. Even their individual motives in joining the Legion varied greatly. They came from surprisingly different social backgrounds: some of them were brought up in state homes and orphanages, others came from large peasant and worker families, but there were also children with intellectual, middle-class, and even aristocratic family backgrounds, whose ancestry was a source of constant discrimination and humiliation under communist rule. In Hungary, many of them had dropped out of school and were forced to take poorly paid, slave-like work in mines and factories; others were put behind bars in their early teens for rebelliousness, vagrancy, petty theft, or simply for trying to escape to the West through the Iron Curtain.

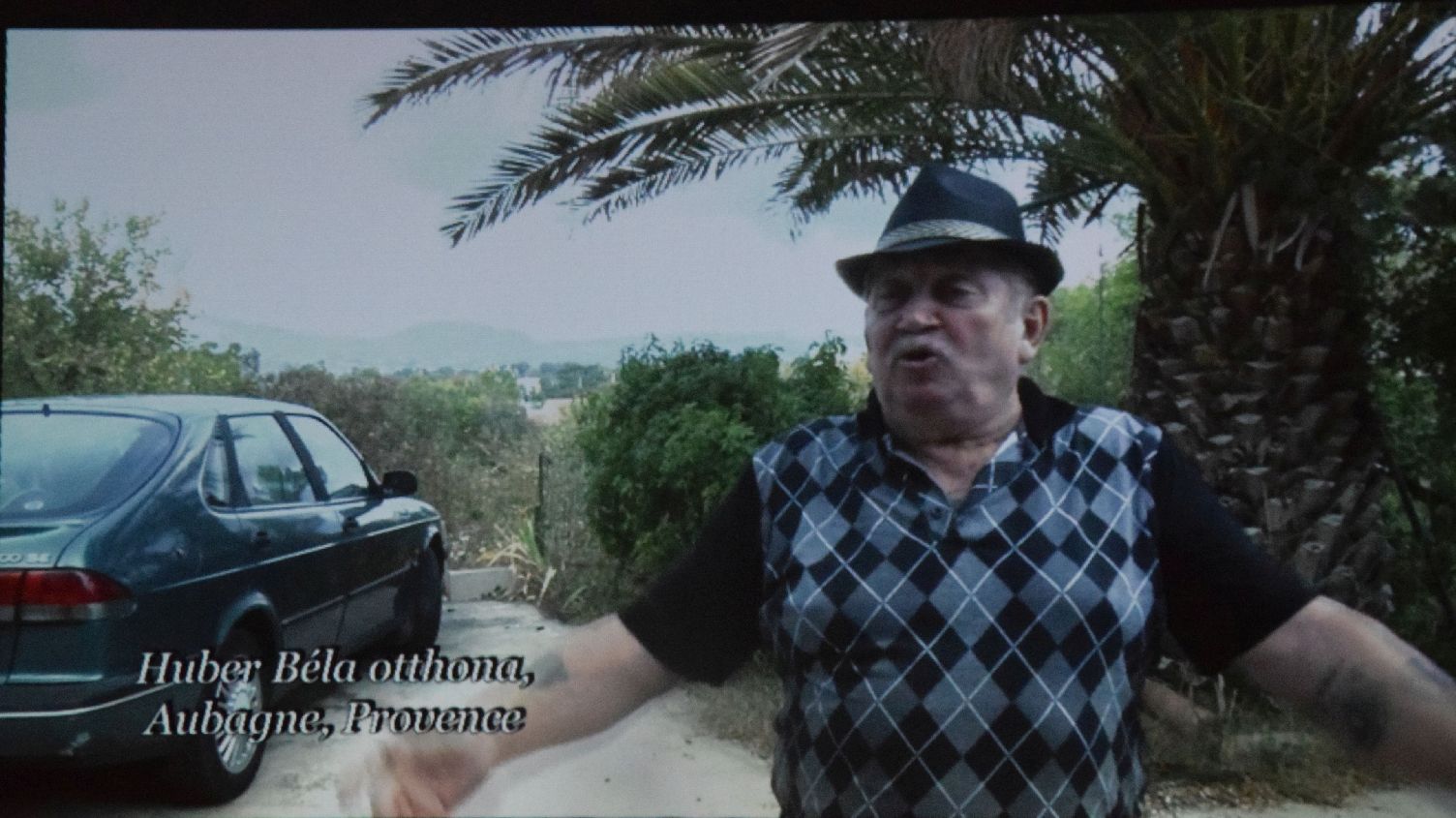

Thus in the autumn of 1956 they all joined the protest demonstrations and the revolutionary unrest with great enthusiasm. Now, on average over 75 years old (as of 2018), they still remember this time as their “baptism by fire.” The then thirteen-year-old János Spátay volunteered as a courier, passing secret messages sewed in a football from the isolated revolutionary troops across the bridges of Budapest that were blocked by Russian tanks. Fourteen-year-old Béla Huber from Sopron was the first to throw a hand grenade at the local headquarters of the secret police (ÁVH); he continued to hide out in the woods along the western border with other teenage boys for a month after the adult insurgents had all fled to Austria. Sixteen-year-old Gyula Sorbán took up arms on the first night at the siege of the Radio headquarters and for days was busy producing Molotov cocktails until he was gravely injured in the leg by a Russian tank grenade. Sándor Soós, a 17-year-old apprentice miner in Oroszlány protected the entrance of the New York Palace, a hotel and press center in downtown Budapest, with a light machine gun and only fled to the West with the last group of insurgents one week after the second Soviet military invasion started.

The boys mentioned above, together with many of their would-be fellows in the Legion, happened to know each other in Hungary, but became close friends only when they met again in North Africa during the Algerian war. Those many Hungarians who had joined the Legion a decade before, at the end of World War II, were mostly teenage prisoners of war in French camps and had experienced the ravages of war in Indochina; the volunteers after 1956 served rather in Algeria and subsequently in Corsica, Chad, Madagascar, Tahiti, and other places. To begin with, all recruits signed a contract for five years, but there were many who did not serve their time. Some deserted after a few weeks, others served long enough to qualify for permanent residence in France or French citizenship; at least one was awarded a pension after 15 years and eight months service; others ended their 15–30-year career as ensigns, the highest ranking warrant officer in the Legion, and as a rule only awarded to French citizens. However, one in every four Hungarian legionnaires deserted or attempted to do so, especially after mid-1958 when the war in Algeria increased in cruelty.

Why then did so many young refugees choose to join the Legion? The seduction of popular pulp fiction may be one reason, but there were more compelling factors, particularly for those who had fought and fled in 1956 and feared reprisals if they returned; experience showed these fears to be well-grounded. And thus for many of them the motto of the legion, Legio [est] patria nostra, was more than a slogan: the Legion became their new home for many of those young apatride.

In tracing the lives of the teenagers who fled to the West in ’56, one can see clearly all the emotional and moral dilemmas involved in their personal decisions and through these events: the sporadic socialization of this hard-lived generation, its repeated failure at adapting, and the attendant identity crises. They also reflect on their native land, the Legion, and their host country. Though their loyalty to the former two seems to remain firm, similarly to their stubborn anticommunism rooted in their early youth experience of the Hungarian revolution, they felt much more reserved and were often critical of the French public affairs and way of life, as both are missing “the real” patriotic loyalty and altruistic attitude. Thus, keeping alive the regular meetings and traditional community rituals, with their strong 1956 engagement, served to strengthen the Hungarian legionnaires’ moral and cultural resistance.

Their personal documents together with the overall research collection of Béla Nóvé was donated to Blinken-OSA Archives, Budapest, then organized, catalogued, and archived in 2017–2018, and is now open to the public.